In his last book, “Stay the Course,” Jack Bogle left investors and professionals a warning about a coming battle in investment management.

He had been watching closely over the past few years as a growing number of academics raised questions about the size of big passive fund managers, such as Vanguard, BlackRock and State Street Global.

As they grow, will they control too many of the voting shares of America’s largest corporations to the extent that they tamp down competition? It’s a question that could shape regulation of the mutual fund industry over the next decade or longer. Some proposals are already calling for rules that would determine which funds could own shares of which company, which would, Bogle pointed out, defeat the very idea of an unmanaged fund — the index fund.

He was deeply worried that in trying to solve the structural problem, regulators and industry would forget about the main beneficiaries of index funds: the people he called “the little guy,” middle-class investors.

“In the years ahead, all of those interested in the future of investment management must join the fight against largely unsupported theories that would … destroy the single best option that our families have for investing to accumulate wealth: buying and holding shares in a broadly diversified, low-cost stock market index fund,” he wrote.

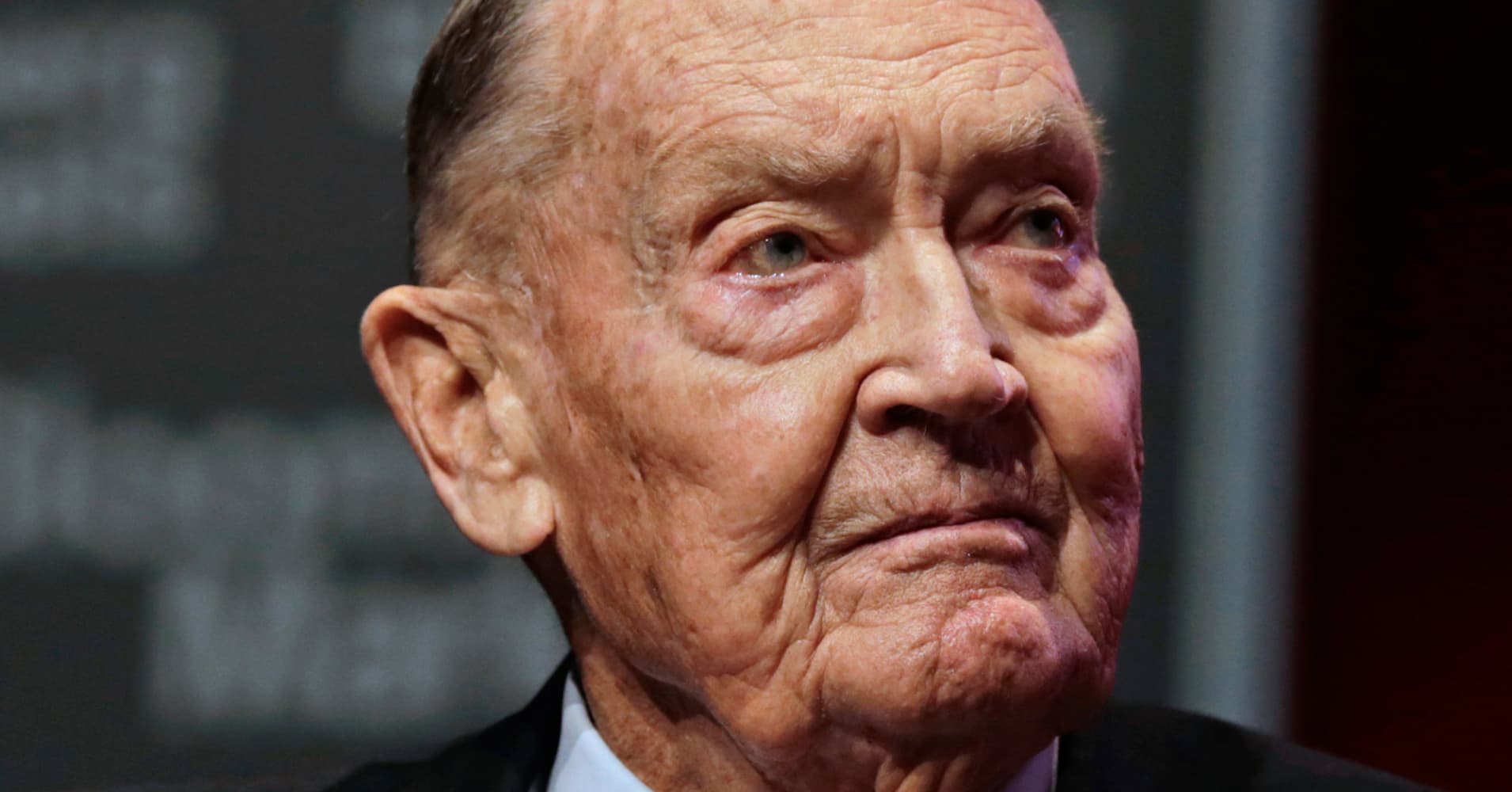

I interviewed Bogle, who died on Wednesday, Jan. 16, about a half-dozen times over the past five years. I’ve interviewed hundreds of CEOs over the course of my career; Bogle towered above most every business leader. He was a lion of the investing world, one of the 20th century’s most influential people. But what stood out about Jack personally was his sense of values, the nuanced way he thought about them and how hard he worked to maintain them.

Jack was always standing up for the little guy. Under the exterior of the world-famous CEO, I found him a kind and thoughtful man.

I interviewed him first when I was newly divorced, with two kids, no job, very little money and a scrap of an idea that I could make it as a freelance writer. Jack and I did a good phone interview — he laughed and reminisced about the bike he’d saved for as a kid. Then I took courage into my hands and asked if he’d sit down for an in-person.

I arrived at the office and immediately discovered I’d forgotten to bring a pen. “What kind of writer are you?” he rasped, sounding grouchy. The low coffee table in his office was covered with papers. He’d been calculating how low fees correlated to higher returns.

But somehow we wandered into personal territory. He hadn’t grown up rich, he told me. In fact, his mom worked in a gift shop to put food on the table during the Great Depression. “You just can’t imagine the burden she had day after day,” he said. “I don’t ever recall her complaining. Life has a lot of burdens. She never showed them.”

I teared up, thinking about the way mothers try to hide their pain from their children and how the children almost always know. “I’m a single mom, too,” I said, aghast at my own lack of professionalism. “I’m so sorry.” The grouchy CEO melted way. He started to cry, too.

Be the first to comment